|

Dear LA County Community, (En EspaŮol)

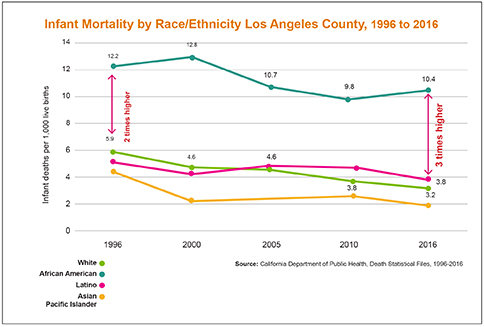

BARBARA FERRER PhD, MPH, MEd DIRECTOR, LOS ANGELES COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH FEBRUARY 1, 2019 One of the most profoundly troubling indicators of racism is the differences in rates of infant deaths across races. Black infants in the United States die in the first year of life at approximately twice the rate of whites. In Los Angeles County, the gap is even more pronounced: Black infants die at 3 times the rate of white and more than 3 times the rate of infants of mothers of Asian descent. Today, if Black babies had died at the same rate as white babies over the past decade in LA County, there would be 640 additional children alive today who could grow up and become presidents, artists, clinicians, teachers, public safety workers or business leaders. That is an entire elementary school of children lost.

A large body of research indicates that the chronic stress (and its impact on health) of racism experienced by Black women generally and of economic hardship experienced by Black women disproportionately, underlies that risk. And compounding the impact of racism in the broader society, Black Americans are less likely to receive quality medical care than whites, and Black mothers frequently report neglectful or dismissive treatment on the part of providers.

The lived experience of infant mortality is devastating. There are many Black women in our community Ė our friends, colleagues, neighbors, sisters, daughters and mothers Ė who have experienced the trauma of high risk pregnancies or the loss of their child. In the last year, two articles, one in the New York Times and one in the LAist, told compelling stories of what it is like to be a pregnant Black woman experiencing complications and the loss of an infant. I recommend reading them both; they are important pieces of journalism that shine a light on some of the ways racism has life and death consequences. While the LA County Department of Public Health canít solve this complex problem on its own, we can acknowledge the devasting impact of racism and intervene in important ways that can make a difference. We have developed a strategy that is rooted in promoting racial justice and designed to reduce the chronic stress in womenís lives, prevent social stress from translating into psychological stress, and intervene as early as possible when stress has taken a toll on health. Some of the changes we are making include:

As a community, we can all play a role in contributing to an environment that supports healthy adults and children. Using empathy in our day-to-day lives for every person we encounter contributes to a community that respects and cares for one another. You can also learn more about your own Implicit Bias by taking one or more of these tests. Connect with these organizations to join efforts to advance economic, social and racial justice. And we can all challenge stereotypes that blame Black women for what is, in fact, a failure of our society. When I think about my own pregnancies, and what enabled me to give birth to two healthy infants, itís clear that a whole set of supportive circumstances were in my favor. I was a relatively young mother, pregnant with my first child at 23, and my partner and I were community organizers. Although we didnít have much money, I had good health insurance and lived in a caring community. And while I am Puerto Rican, I have white skin, and enjoy all the privileges that come from being white. This included having providers who looked like me and treated me respectfully, living in a 'safe' neighborhood with little or no hazardous environmental exposures, and being treated courteously at stores and work. It also included having the knowledge that family members had the resources to back us up if we ran into a crisis. Every woman should have similar opportunities and has the right to have the support and care she needs to have a healthy birth and raise a healthy child. Keep in touch with me through social media. Iíd love to hear your ideas on creating a community that supports healthy women, children and families.

Until next month, wishing you peace and health,

|

|

Years of scientific research show no inherent biological reason for this inequality. In fact, when we look at babies born to immigrants to the US from Africa, they donít die more frequently than whites. When we look at US-born Black babies, however, the inequality has persisted over time and across communities. Common explanations for this disparity donít stand up to scrutiny. Research shows that itís not bad mothering or lack of knowledge on the part of Black women that makes the difference. So what does explain it?

Years of scientific research show no inherent biological reason for this inequality. In fact, when we look at babies born to immigrants to the US from Africa, they donít die more frequently than whites. When we look at US-born Black babies, however, the inequality has persisted over time and across communities. Common explanations for this disparity donít stand up to scrutiny. Research shows that itís not bad mothering or lack of knowledge on the part of Black women that makes the difference. So what does explain it?

This pattern started long ago. African American communities have historically experienced high rates of infant mortality compared to other races in the US, dating back to a time when Black women were enslaved in the United States. It has continued through the decades, reflecting a troubling history of mistreatment of Black women through slavery, exploitation, forced sterilization and other abuses that are devasting to physical and mental health.

This pattern started long ago. African American communities have historically experienced high rates of infant mortality compared to other races in the US, dating back to a time when Black women were enslaved in the United States. It has continued through the decades, reflecting a troubling history of mistreatment of Black women through slavery, exploitation, forced sterilization and other abuses that are devasting to physical and mental health.